Lalgarh: The Pawn In A Dangerous Game

Posted by Admin on October 2, 2009

From Tehelka Magazine, Vol 6, Issue 40, Dated October 10, 2009

Chhatradhar Mahato could have played Lalgarh’s peace broker. Now his arrest may fuelmoreviolence. TUSHA MITTAL & SUMAN BHATTACHARYA report

Negotiator Mahato (seated at right) with Bengal’s intelligentsia in Lalgarh in 2008

Negotiator Mahato (seated at right) with Bengal’s intelligentsia in Lalgarh in 2008

Photo: PINTU PRADHAN

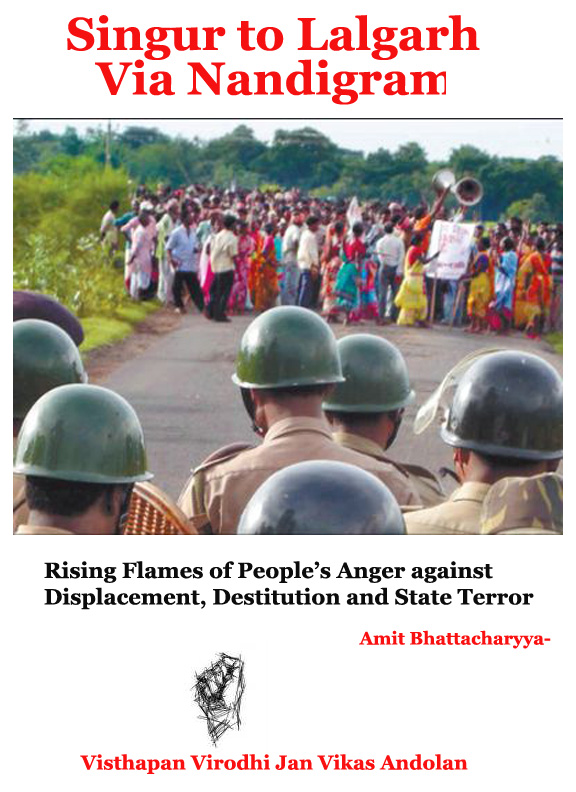

AROUND 20 KM from Lalgarh, the battle lines are clearly drawn. It is March 2009 and thousands of adivasis are assembled outside a remote village called Saranga in West Bengal’s West Midnapore district. They are facing an enormous contingent of policemen with guns and riot shields at the ready. If the tribals dare march any further, the police will fire.

Days earlier, the adivasis were scheduled to hold an organised peaceful rally in Saranga village. The police imposed Section 144 and arbitrarily arrested several tribals. Now, the tribals have organised themselves again. They want to march into the village to assert their rights, but the police will allow no such freedoms.

Just when the mass begins to get impatient and unruly, a thin spectacled man emerges on top of a cycle van. In a three-minute speech he tells the tribal community that they must continue to fight for their rights – but not today. Going ahead will only mean more bloodshed for their own kin. At this moment, they must avoid the impending confrontation. “Let us march back in a disciplined manner,” he says. Within minutes, the masses begin the long trek back to their huts and fields.

This man is Chhatradhar Mahato, 45, a local political activist who rose to the fore in November 2008 when Lalgarh was no more a nondescript village in the remote interiors of Bengal. A suspected mine blast by Maoists on CM Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee’s route had triggered brutal police oppression and arbitrary arrests in the area. Thousands of adivasis across political lines aligned under a banner called the People’s Committee Against Police Atrocities (PCAPA), an indigenous people’s movement fighting to restore dignity to the adivasi community. They vowed not to let the police enter their lands until the state and the police formally apologised to them.

“Mahato was initially just a participant, but it was the movement itself that thrust him up as a leader,” says Partho Ray, a professor in Kolkata who was part of a fact-finding mission to Lalgarh. “Mahato took the initiative to give the movement an organisational structure and played an important role in forming the committee,” he says. Mahato soon became the spokesperson for the PCAPA and the face of the tribal resistance against the police.

When time came for parliamentary elections in Bengal in May 2009, it was Mahato who met with the state’s Chief Election Commissioner. Mahato wasn’t opposed to free and fair elections, but he wouldn’t allow the police to enter Lalgarh. “We will not allow any central force to visit Lalgarh since they work under the guidance of the state government,” he said, but added, “we assure the officials they will not face any trouble on polling day. We will provide them with adequate security.” After several meetings, a middle ground was reached — the election booths would be placed outside Lalgarh and the tribals would allow the police to man these booths.

It is this ability to accept the middle ground vision that distinguishes Mahato from the Maoist ideology that completely rejects the State. That is why Mahato’s arrest last week under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act on charges of being a Maoist sparked fresh uproar in the region. But Mahato is no stranger to the ways of the State. He had already dared the Bengal government to arrest him. “I have not fled anywhere. I am in Lalgarh, let them come and arrest me. It will not stop the people’s movement,” he had said.

Several of Bengal’s intellectuals such as Mahasweta Devi, Prasun Bhowmik and Sukhendu Bhattacharya along with 19 local organisations have now issued a memorandum demanding his unconditional release. “Arresting him means crushing a democratic protest,” says filmmaker Aparna Sen. “When you do that, it forces people to take to violence.”

| On Mahato’s call, the mob stepped back from an imminent clash with the police |

POSING AS journalists from Singapore, the Bengal police arrested Mahato on September 27 on charges of leading an anti-administration movement, giving shelter to Maoists and the murder of CPM activists. There are a total of 22 charges against him. In mid-September, Chhatradhar’s younger brother Anil Mahato was also arrested on charges of murdering CPM activists. “Chhatradhar and Kishenji (a Politburo member of the CPI Maoist) are linked. They have met a number of times. Chhatradhar has a lot of illegal properties in Mayurbhanj, Orissa, under false names. He has admitted it,” says Bhupinder Singh, DG, West Bengal Police. Adds CM Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, “Formally, his name might not be on the [Maoist] organisation’s list, but by forming the Sangram Committee (the PCAPA), he has provided an open forum for Maoist activity in Lalgarh and its surrounding areas.”

Born in Amlia village, two kilometres away from Lalgarh, Mahato went to school in Lalgarh and enrolled in a bachelor’s degree course in Midnapore College. It is said his father Buddhiswar Mahato — who continues to live in Amlia today — was a Naxal leader of the 1970s. But there were many other local land rights struggles escalating in Bengal during the Naxalbari uprising; this could easily be another mistaken identity. Mahato dropped out of college in 1996 and joined the Chhatra Parishad, a youth wing of the Congress party. Two years later, when the Trinamool Congress began making inroads into Bengal’s interiors, Mahato switched over. It is unclear how long his association with the TMC lasted or why he broke away. “He left the TMC to form his own people’s party. We do not approve of the way he has been arrested by the CPI(M) government, but what he is doing is also not in accordance with parliamentary and democratic politics,” Partho Chatterjee, Leader of the Opposition in Bengal told TEHELKA.

| ‘I am in Lalgarh. Let them arrest me, it will not stop the movement,’ Mahato had challenged |

The PCAPA has often been accused of being backed by the Maoists, although there is no evidence to prove it. That Mahato may have Maoist sympathies cannot be ruled out. His elder brother Sashadhar joined the CPI (Maoist) in the 1990s and has been underground since. That the PCAPA may have members who have Maoist sympathies or Maoist links cannot be ruled out. But by arresting Mahato without any credible evidence, the Bengal police have only alienated the tribals of Lalgarh further. Mahato could have been their bridge into the tribal community; perhaps a medium to draw the tribals out of the Maoist influence. Now the Bengal police have only pushed the people of Lalgarh further towards extremism.

“Unless Chhatradhar Mahato is released unconditionally, the entire Jangalmahal (a forested belt) in five states [West Bengal, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Bihar] will be up in flames,” Kishenji said recently. “A hundred other Chhatradhars will be created to carry on the activism.” And none of them may be willing to meet the state’s Chief Election Commissioner.

Leave a comment